Exploring ultramarine

Exploring ultramarine

Notes from a two-day workshop on ultramarine

Anita Chowdry, David Margulies and Marinita Stiglitz

Bodleian Library, MS. Elliott 287, fol. 34a, a young man picking a blue rock from the ground

Introduction

In his travels Marco Polo vividly described the cold province of Badakhshan, a prosperous land, where horses that descended from Alexander's horse Bucephalus were once bred and where priceless rubies and the finest lapis lazuli were found.

Since ancient times lapis lazuli has been sourced in this remote region, north-east of modern Afghanistan, and exported over vast distances. Its mines, high in the steep Hindu Kush mountains, above the Valley of the Kokcha River, can only be reached through a tortuous and dangerous route. At present only the mines of Sar-e-Sang have reserves of the highest-grade lapis lazuli. Other historical sources are near Lake Baikal in Siberia. The other locations where lapis lazuli can be found in commercial quantities are in the Andes Mountains of Chile and in Colorado, USA. There are smaller deposits on Baffin Island, Canada, in Lazio, Italy, and in the Pamir mountains of Tajikistan.

Before the use of explosives, the mining of lapis lazuli involved lighting large fires against the rock and, when the rock was hot, throwing cold water onto it. The sudden cooling caused the rock to crack and split enabling the extraction of the lapis lazuli from the marble matrix with pick, hammer and chisel.

Lapis lazuli consists of a large number of minerals, including the blue mineral lazurite, the white mineral calcite and golden specks of iron pyrites. Samples of this opaque semiprecious stone vary considerably in appearance and quality, from the most prized deep blue pieces sometimes speckled with pyrites to the less desirable pale mottled blue and white pieces.

Examples of different grades of lapis lazuli: lazurite crystals or nodules in calcite matrix with golden pyrite specks and very pure rock with pyrite golden strikes, both from Afghanistan. The third sample in a highly impure rock, most of which is calcite, from Chile.

This valuable commodity, much prized since antiquity, has been used to carve artefacts and jewellery; legend has it that it was powdered as a cosmetic eye shadow favoured by Egyptian women and later employed to make the pigment ultramarine.

A laborious process transforms this composite mineral into the pigment ultramarine; various grades of ultramarine can be obtained, from the purest extremely expensive deep blue to the pale grey, so-called ultramarine ash.

Different grades of ultramarine from rich blue on the left to pale grey on the right

Preparation of ultramarine from lapis lazuli under the guidance of David Margulies

During the workshop two batches of ultramarine were prepared, one from so-called lazurite crystals and the other with high grade lapis lazuli rock and the results compared. Grinding and levigating (a term used for the separation of the different particles using water) was sufficient to produce a rich blue pigment from the very high quality mineral.

Left to right: lapis lazuli crystals, crushing, grinding.

Left to right: levigating, deposited ultramarine, and ultramarine.

As both crystals and rock are very hard materials, they had to be reduced in size with a hammer before the grinding with pestle and mortar could take place. During the grinding process the distinctive odour of sulphur was produced by the breaking down of the lazurite particles. As the complex mix of minerals is broken down the powder appears to become paler and paler, in part due to the quantity of transparent minerals to be found in lapis lazuli, and partly due to the release of some of the sulphur found in the different minerals. The purified blue pigment extracted from lapis lazuli is essentially the mineral lazurite which is a complex sulphur-containing aluminosilicate.

Whilst grinding with pestle and mortar we noticed that the crystals were relatively soft and brittle and were easier to break compared to the hard lapis lazuli rock. Once a coarse powder was obtained with a granite pestle and mortar grinding continued with a ceramic pestle and mortar adding water to obtain finer particles.

The final grinding with water was done with a polished alabaster pestle and mortar; at this stage the water was poured out leaving the purer heavier particles in the mortar. The resulting pigment was washed several times to purify the lazurite further. The pigment was left to settle in water so that the heavier lazurite particles slowly deposited on the bottom of the vessel while the other components could be poured off with the water, leaving a purer pigment behind. This process was repeated until a rich saturated blue was left at the bottom of the vessel. The batch of pigment obtained from the rock required several further washing before a rich blue could be achieved.

Preparation of ultramarine for painting under the guidance of Anita Chowdry

During the workshop we were able to examine illuminated and illustrated pages in a number of manuscripts from the Bodleian Library collection. These included European, Persian and Armenian examples dating between the 14th and the 18th centuries, all of which contained extensive use of lapis lazuli pigment of various tones. Pigments in manuscripts were mixed with a variety of binding media depending on where the paintings were made- for example they could be tempered with glair, animal glue or gum Arabic.

Painting with ultramarine presents practical difficulties. Some of the colour variations may be due to how the paint was prepared, as much as the quality of the pigment itself or the mineral sample from which it is made.

To make paint suitable for Persian illumination on paper, the pigment needs to be milled as finely as possible and tempered with gum Arabic. We used a sheet of ground glass and a heavy glass muller for this process. A quantity of prepared pigment is placed on the glass and moistened with a few drops of water, then ground with the muller using a steady circular or figure-of-eight motion. As the mulling proceeds, the grating sound of it passing over the pigment begins to subside as the particle size is reduced, and the pigment may start to give off a sulphurous odour. At this point the binding medium is added – a few drops at a time, and the mulling continues. The texture of the pigment becomes discernibly smoother and silkier. The pigment is tested repeatedly during this stage by painting a small streak onto paper and allowing it to dry. When dry, the test sample is rubbed with a finger – when it ceases to powder off or smear, is an indication that it contains sufficient binder.

Dry ultramarine pigment

Mulling ultramarine with gum arabic

The handling and texture of the paint is improved by the addition of a tiny drop of honey, which acts as a wetting agent, and a drop of full-fat milk, which helps to homogenise the colour. These additions to the pigment also have the effect of enriching the colour. A little more gum Arabic or milk than is strictly necessary can be added to further enrich the colour and increase its viscosity, which leads to speculation that this may often have been done with deliberation in some of the manuscripts. In 'Il libro dell'arte', attributed to Cennino Cennini, it is suggested that one could enhance the colour with the addition of kermes or sappanwood. The two illuminated pages below show different applications of ultramarine, reflecting variations in the overall aesthetic of the respective styles of illumination.

Looking at manuscripts

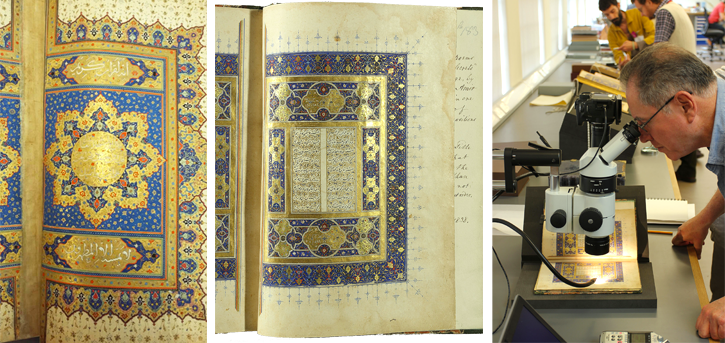

MS. Arab. d. 98 – dated to the 16th century CE, possibly from Safavid Iran – is a manuscript copy of the Holy Qur'ān. It shows an exuberant aesthetic with extensive areas of gold setting off fields of ultramarine that are very bright and saturated, close to the colour of a high quality pigment with minimal additions of gums and wetting agents.

Left to right: MS. Arab. d. 98, fol. 1b, MS. Elliott 287, fol. 1b, and David Margulies at the microscope

MS. Elliott 287 – dated to 1485 CE, late-Timurid period from Herat, modern-day Afghanistan – is a manuscript of a poem in Chaghatai (Eastern Turkish). It shows an earlier aesthetic which favoured a restrained palette dominated by ultramarine that is deep and rich in colour, setting off complex passages of Arabesque design. The pigment would need to have been exceptionally finely divided and smooth flowing in order to navigate such virtuosity; that fact added to its richness of hue suggests that it may have been mixed with a greater proportion of binding medium.

Ultramarine paint is challenging to work with partly because of the shape of the particles, which are predominantly irregular or conchoidal (that is to say 'curved fractures'), and also because of its density. Tempered with gum Arabic, it in no way handles like modern watercolours. In a water-based medium it is intensely opaque and has great covering power, but at the same time the heavy particles are highly resistant to smooth application, because of their shape. It is also resistant to the application of other colours or gold on top of it, which tend to sink below the surface of the ultramarine ground. It is also fairly resistant to burnishing, a treatment which is routinely applied to most colours in the painting of Persian manuscripts, this again is because of the individual particle shapes.

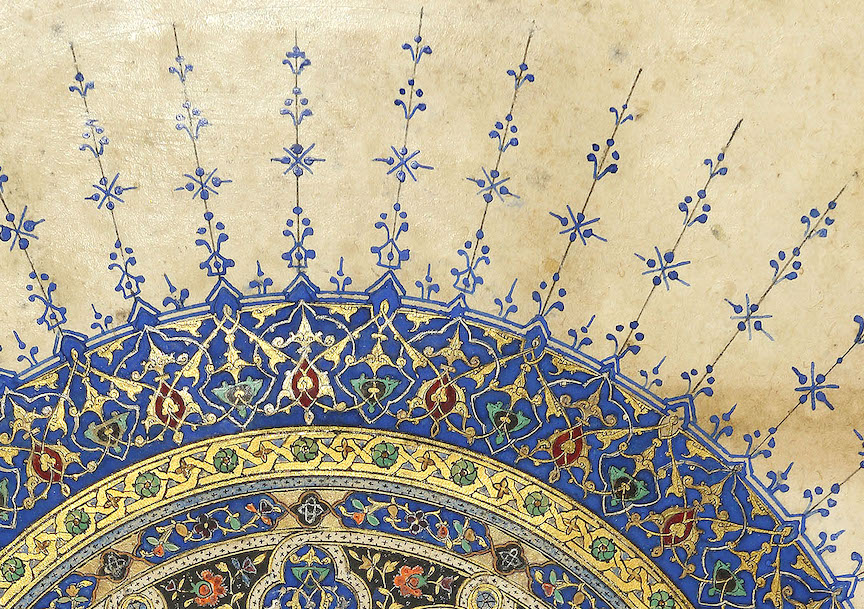

Detail of Bodleian Library MS. Arab. d. 98, fol. 1b with golden florals joined by barely visible golden spirals

This tendency is clearly borne out in MS. Arab. d. 98, in the gold details applied to the central ultramarine ground. The heavily applied gold florals sit freely over vegetal spirals that are barely visible because they have sunk below the surface of the ultramarine ground. However, the ultramarine is remarkably evenly applied. This suggests a technique called 'floating'', in which the paint is first diluted to a watery consistency, and then rapidly blocked in using broad sweeping strokes with a large, fully loaded brush. It is allowed to dry undisturbed and, as the water evaporates, the particles of pigment settle evenly on the surface of the paper.

MS. Elliott 287 displays a rigorous classical technique in which every detail of the gold and polychrome Arabesque design is executed first, and the ultramarine is then very carefully painted in around the design afterwards.

Detail of Bodleian Library, MS. Elliott 287, fol. 1b

Arabesques designs worked up in detail and burnished before the application of the ultramarine ground by Anita Chowdry

Ultramarine is also used for ruling lines in Persian manuscripts. It can be seen in the structural lines of page layouts, and also in a decorative device known as tigh or 'spears' that project outward from the outer boundaries of a design. This can be seen in MS. Elliott 251, an undated manuscript of a poem in Persian written for Abū l-Fatḥ Pīrbūdāq Bahādur Khān (c.1450 CE?). While the paint of the decorative lines usually shows the same consistency as that of the main body of ultramarine, structural lines are at times darker with a more ink-like consistency, suggesting that the pigment was modified in some way for this purpose.

Detail of Bodleian Library MS. Elliott 251 (fol. 1a), showing ultramarine 'spears' radiating from a circular shamsa motif